Early Childhood EducationIdentifying the roots of educational disparities in Baton Rouge

letter from braf’s

ceo chris meyer

Learning is a lifelong endeavor – one that begins before kindergarten and continues long after graduation. Success in education is one of the strongest predictors of lifetime opportunity. Unfortunately, many local children are not provided with adequate resources to live up to their educational potential.

Research shows that the building blocks of education are set in the first few years of a child’s life, with 90% of brain development happening before the age of five. Consistently, studies show that the greatest return on public and social investments are those made in early childhood education and development. In East Baton Rouge Parish we’ve accomplished the enviable feat of enrolling nearly every four-year-old in pre-kindergarten programming. However, most of these students arrive in kindergarten unprepared to start school.

Over the last few months, the Baton Rouge Area Foundation along with our data science partners at Common Good Labs, embarked on one of the largest studies in the country on the connection between educational opportunities and other outcomes such as future justice involvement, economic mobility, and life expectancy.

The following brief is the first of a multi-part series on improving education for children in East Baton Rouge Parish. It offers insights on national trends and detailed analyses of local student performance. This research helps reveal the existing strengths in East Baton Rouge Parish’s educational system and outline clear opportunities for improvement for our students.

This is an inflection point for our community. With these new findings, we can choose to reject the status quo of poor educational outcomes, and instead work together to adopt data-driven methods for preparing our youngest learners for school success.

Onward,

Chris Meyer

President and CEO

Baton Rouge Area Foundation

INTRODUCTION

This community briefing was created by the Baton Rouge Area Foundation and Common Good Labs as part of the Opportunity Data Project. It is designed to help local residents understand why many children fall behind in early childhood and have difficulty catching up with their peers in East Baton Rouge Parish.

The analysis in this report comes from one of the largest datasets in the United States on local education. The Baton Rouge Area Foundation and Common Good Labs worked with the East Baton Rouge Parish School System and the East Baton Rouge District Attorney to assemble data on educational outcomes and involvement in violence among local children. This data covers more than 15 years of time and provides a comprehensive perspective on local educational systems within the parish from age four to 18.

The first section of the brief shares three important lessons drawn from existing research on early childhood development. The second offers analyses of the current challenges and opportunities in East Baton Rouge Parish.

There are

three facts

that local residents should understand about early childhood development within

the United States.

Fact #1.

Approximately 90% of brain development occurs before a child turns five.

Comparison of brain development by age

During the first five years of life, a child’s brain will more than triple in size. By the time a kindergartener starts school, their brain has completed 90% of the growth that will occur during their entire life.1 This rapid growth enables children to learn at an incredibly high rate during early childhood. The knowledge and skills they build are seen in a number of ways.

Cognitive development. In the first months of life, children begin to recognize familiar sounds and faces and start to babble. By the time they are approaching five years old — just a few years later — most children have learned to speak in complete sentences, have developed problem-solving skills, and understand concepts like numbers and spatial directions.2

Social and emotional development. Newborn children can only express themselves by crying and have little ability to recognize the emotional expressions of others. As their brains grow, they become more expressive and learn to interpret others’ emotions. When children reach four to five years in age, most can form friendships, understand social norms, and display some ability to regulate their own emotions.3

Motor skill development. At birth, children can only turn their heads and possess limited control of their own arms and legs. Within a few years, they learn to crawl and then walk. As they reach five, the average child can run, skillfully manipulate small objects with their fingers, balance on one foot, and operate compound machines like tricycles.4

Because these changes are common, it is easy to overlook how dramatic they are. The amount of learning that can occur during early childhood is nothing short of miraculous.

Though 90% of brain development occurs between birth and age five, only a small fraction of public spending on education is dedicated to children during these crucial years.5 For the most part, families in the United States must pay for early childhood education or provide it directly themselves. This can have great consequences for students from low-income families who lack resources and often have less time at home to invest in their children’s development.

Fact #2.

Development gaps often form in early childhood between students from low-income families and their peers that persist throughout childhood.

There is a substantial early childhood development gap between students from low-income households and those with greater incomes in the United States. Research has found that toddlers in lower-income families have vocabularies that are 30% smaller than those of their higher-income peers.6 Another study found that five-year-old students from low-income families are around one year behind their peers in tests of language development, on average.7

Similar research has identified significant disparities in social and emotional development as well as other measures of learning in early childhood based on family wealth. A long-term study of early childhood environments and readiness for kindergarten concluded that children’s “levels of readiness and development are closely associated with their parent's socioeconomic status.”8

There are likely many reasons these differences exist. Families with less income are unlikely to be able to afford high-quality preschool programs. Children in these families more frequently lack access to nutritious food and are more often exposed to environmental toxins and stressful events that can slow their development.9 Parents in low-income families also tend to have lower levels of education themselves, which makes it more difficult for them to support their children’s development.10

Though mothers and fathers in low-income families want the same things for their young children’s education that wealthier families do, they often face multiple barriers like these.

When students from low-income families fall behind in early childhood development, it can be very difficult for them to catch up to their peers. Researchers have found that the lack of language skills before starting kindergarten is one of the primary reasons why students from low-income families tend to have lower educational performance in elementary school.11 Studies also indicate that lower performance in elementary school is associated with higher rates of dropping out in middle school and high school, lower earnings in adulthood, and an increased likelihood of becoming involved in violence later in life.12

This is largely because children who are unprepared for kindergarten are more likely to be unable to read by the end of third grade. As experts have noted, from kindergarten through third grade children must learn to read because after third grade they must read to learn.

Fact #3.

Programs that support early childhood development in students from low-income families can be highly effective, but program quality is critically important.

Cost-benefit analyses of investments in early childhood education

Total return per $1 invested

Students from low-income families can close the early childhood development gap if they are provided with effective support. While there is no single one-size-fits-all formula for how to best assist young children, many of the most successful programs focus on infant and toddler health, as well as educational assistance. This is seen in three of the most well-known models studied in the United States.

Nurse-family partnerships. This program provides first-time mothers with home visits by nurses from prenatal stages until the children are two years old. Analysis indicates that it can lead to significant improvements in cognitive and language development in early childhood.13

High-quality preschool education for three- and four-year-olds. Researchers have studied pre-kindergarten education programs (also known as “pre-K”) for three- and four-year-olds that also include weekly teacher visits focused on educational play. A longitudinal analysis found this combination of support can lead to higher IQ scores, greater educational attainment, and increased earnings in adulthood.14

Complete early childhood education from infancy to age four. An experimental study found that providing early childhood education for all five of the first years of early childhood significantly improved cognitive and academic outcomes for students from low-income families. These effects persisted well into adulthood.15

Interventions like these are very cost-effective. Cost-benefit analyses suggest that for every dollar spent on the three programs listed above, communities earn back between $3 to $9 of direct benefits through lower levels of crime, less spending on remedial educational programs, and greater tax revenue due to increased earnings in adulthood.16 In fact, an analysis of cost-benefit evaluations of more than 100 government initiatives focused on improving well-being found that public programs to support early childhood development and health provide the most consistent benefits per dollar spent of any government program.17

However, not all early childhood programs are equal. Ensuring that programs have high standards of quality is critical for their success. Pre-K programs are one of the most universally adopted early childhood development initiatives in the United States. Numerous studies have shown they are often quite effective, but even these programs can fail if they do not maintain a high level of quality.

This was illustrated in a recent study from Tennessee. It found that children who participated in the state’s public pre-K program had worse academic and behavioral outcomes later in elementary school than those who did not participate.18

Analysts suggest that this was likely due to the fact that Tennessee’s program was relatively underfunded — likely leading to a high student-to-teacher ratio — and used a lower quality curriculum.19

There are

three facts

that local residents should understand about early childhood development in

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH.

Fact #1.

In Baton Rouge, large numbers of students from low- income families arrive at kindergarten far behind their peers.

Kindergarten readiness assessment scores: U.S. average vs. students from low-income families in the East Baton Rouge Parish School System

Based on national benchmarks and data from EBRPSS kindergarteners in 2018-19 and 2019-20 on tests of first-sound fluency

Source: Acadience Reading K–6 National Norms and analysis of data from the East Baton Rouge Parish School System.

In recent years, the East Baton Rouge Parish public school system has used an assessment tool to measure students’ readiness to learn to read when they enter kindergarten. This assessment tool measures first-sound fluency by asking children to identify the initial sound at the beginning of a word, such as “mmm” in “mom” or “sss” in “sun.” Each student is scored on a scale of 0 to 60 based on the number of times they correctly identify the first sound in a word during a one-minute test.*

* In the first sound fluency assessment, if a student fails to identify the initial sounds of the first five words the test is ended and they are given a score of zero.

The results of these assessments reveal three striking findings about early childhood development in the parish.

1. A large number of local students from low-income families earned scores on this assessment below the level that is considered ready for kindergarten.† The proportion of incoming kindergartners scoring below this level increased during the pandemic and remains higher than the levels seen in the late 2010s.20

† For the purposes of this analysis, students from low-income families were identified as being those who qualify for federal free lunch status.

2. In Baton Rouge, around one in three students from low-income families who took this test in recent years scored a zero — meaning that they fail to identify the initial sound of even a single word. 21

By comparison, about 13% of children in the country who take this test receive a zero.22 Students from low-income families in East Baton Rouge schools completely fail this assessment almost three times more often than other U.S. students, on average.

3. Over 60% of students from low-income families in the parish who scored a zero on this assessment of kindergarten readiness were not able to read on a basic level by third grade.23

This means that they are likely to struggle in later grades, which require them to have reading skills in order to learn. Students from low-income families who do not read at a basic level in third grade are at a higher risk of future negative outcomes, such as failing to graduate from high school or becoming involved in violence.24

It is important to note that the challenges in kindergarten readiness above are not a universal problem in the community. Students from higher-income families in East Baton Rouge Parish public schools score much better than their low-income counterparts on this assessment.

However, the vast majority of local students from low-income families are concentrated in a relatively small number of public elementary schools, where sometimes as many as half of kindergartners score a zero on this assessment.25 When the majority of students are starting so far behind, it is difficult for teachers in these schools to meet the standard learning objectives during kindergarten, which leaves students behind their peers in later years of elementary school.

Fact #2.

The best opportunity to enhance early childhood education is to improve public pre-K programs for four-year-olds from low-income families in the parish.

Proportion of students from low-income families scoring a zero on kindergarten

readiness assessment in the East Baton Rouge Parish School System

Based on data from kindergarteners in 2018-19 and 2019-20 using test of first-sound fluency with a 0 to 60 point scale

Source: Acadience Reading K–6 National Norms and analysis of data from the East Baton Rouge Parish School System.

Pre-K programs for four-year-olds from low-income families are the largest early childhood program operating in the parish. Pre-K education is divided between two different programs: state-funded centers operated by local public school systems and federally funded centers operated by the city-parish Head Start program.

These programs have impressive reach. Approximately 96 percent of four-year-olds from economically disadvantaged families in the parish are currently enrolled in one of these publicly funded pre-K programs.26 This level of enrollment is a success that should be celebrated.

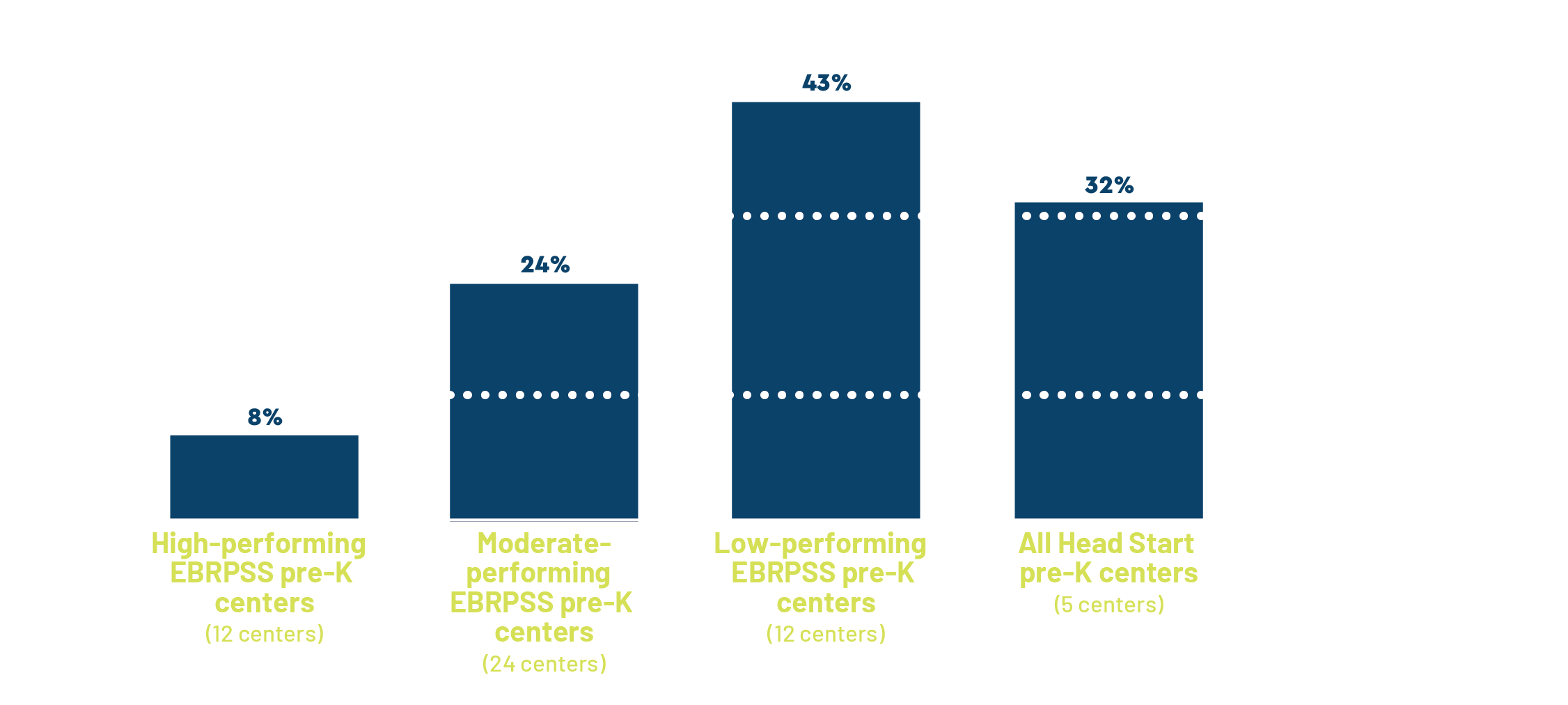

However, local data indicates that some pre-K centers in the parish are much better than others at preparing children for kindergarten. Students from low-income families who attend the highest-performing pre-K centers operated by the East Baton Rouge Parish School System tends to perform slightly better than the national average on kindergarten readiness, with only around 8% of children earning a zero on the assessment described in the previous section.27 This indicates that it is possible to use pre-K programs to help more students from low-income families arrive at kindergarten with higher levels of readiness.

Unfortunately, a significant number of the state-funded pre-K programs are not as effective as these top-performing centers. In the average performing pre-K centers operated by the East Baton Rouge Parish School System, around 24% of children went on to score a zero in kindergarten readiness.28

Even worse, in the lowest performing centers, approximately 43% of children went on to earn a zero on the same assessment.29

Less information is available on the federally funded Head Start program, but the available data indicates its performance is similar to that of the pre-K centers in the parish school system.‡ Data suggests that at least 32% of the students from low-income families who attended Head Start earned a zero in kindergarten readiness in recent years.30 In addition, analyses from the Louisiana Department of Education have found that all five local Head Start centers are not proficient in terms of the instructional support that they offer.31

Research evidence suggests that pre-K programs for four-year-olds can be among the most powerful and cost-effective initiatives for supporting early childhood development among students from low-income families. The Baton Rouge community already receives millions of dollars in funding from the state and federal governments to operate these programs, and they have succeeded in enrolling the vast majority of students from low-income families.

‡ Kindergarten assessment data in the parish groups the children who participate in Head Start together with a second population of children who do not enroll in any public preschool program. Even if it is assumed that all of the students in this second group have the worst possible scores — that every single one earns a zero on the assessment — it would mean that 32% of children in the local Head Start program earned a zero in kindergarten readiness in recent years.

The top-performing local centers demonstrate that it is possible for students from low-income families to have outcomes that match the national average for all children entering kindergarten. The first priority for any local effort to improve early childhood development in the parish should be to lift up all pre-K centers to meet the same standard and prevent so many children from arriving at elementary school and completely failing the assessment of kindergarten readiness.

Fact #3.

The local community can build on a successful four-year-old pre-K program to empower even more students from low-income families to succeed.

In addition to improving public pre-K programs for four-year-olds in the parish, there are several other early childhood initiatives that have significant potential to empower more students from low-income families to succeed. The following three programs are supported by strong research and have been successfully implemented in many similar communities.

Nurse visitation programs to promote early childhood health. These initiatives pair nurses with families that have newborn children to provide education on nutrition, health, and parenting skills. This can include services that begin during pregnancy and often involve home visits with parents and caregivers, as well as referrals to healthcare specialists and social service providers. These types of programs have been shown to significantly improve health outcomes in newborns and infants.32

Parental empowerment to support at-home learning. These programs are designed to enhance early childhood development by focusing on critical learning provided by parents and other at-home caregivers. They provide instruction and support for fostering a stable home environment, helping children build basic language and math skills, and developing instructive and safe play. Studies have demonstrated that these activities provide a strong foundation for later learning and development.33

Expansion of pre-K to include all three-year-olds from low-income families. The evidence supporting pre-K programs for four-year-olds also indicates that there are significant benefits from extending effective pre-K education to include children who are one year younger. The parish already serves some three-year-olds from low-income families through a promising program operated by the YWCA. If more children can participate in learning at the stage of their development, it will build on the efforts made to improve pre-K programs for four-year-olds.34

Conclusion

Though educational challenges in East Baton Rouge Parish persist, there are clear opportunities to better assist young children by improving existing programs and implementing a small number of new initiatives that are already successful in other cities. These changes can help the community to dramatically improve early childhood educational outcomes in the coming years.

NEXT STEPS

The Baton Rouge Area Foundation worked with leaders from across the parish to develop the analyses and recommendations in this brief. The foundation is committed to continue partnering with local stakeholders to implement these ideas and better understand the region’s educational challenges.

The Science of Early Childhood Development.

Systematic review of physical activity and cognitive development in early childhood (Carson, Hunter, et al.).

Developmental Stages of Social Emotional Development in Children (Malik and Marwaha).

Fine Motor Skills.

Who’s paying now? The explicit and implicit costs of the current early care and education system (Gould and Blair).

SES differences in language processing skill and vocabulary are evident at 18 months (Fernald et al.).

Evaluating socioeconomic gaps in preschoolers’ vocabulary, syntax and language process skills with the Quick

Interactive Language Screener (Levine, Pace, et al.).

Inequalities At The Starting Gate (Garcia).

Reducing Poverty without Community Displacement: Indicators of Inclusive Prosperity in U.S. Neighborhoods

(Acharya and Morris).

Parents’ Low Education Leads to Low Income, Despite Full-Time Employment (Douglas-Hall and Chau).

Kindergarten oral language skill: A key variable in the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status (Durham,

Farkas, et al.).

School Dropout Indicators, Trends, and Interventions for School Counselors (Dockery);

Public School Funding, School Quality, and Adult Crime (Baron, Hyman, and Vasquez);

Elementary School Class Rank Predicts Student Outcomes, Economics Study Shows.

Proven Benefits of Early Childhood Interventions (Karoly, Kilburn, and Cannon).

Ibid.

Ibid.

The Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University.

A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies (Hendren and Sprung-Keyser).

Making pre-K work: Lessons from the Tennessee study (Hirsh-Pasek, Farran, Burchinal, and Nesbitt).

Ibid.

Common Good Labs analyses of data from the East Baton Rouge Parish School System.

Ibid.

Acadience Reading K–6 National Norms (Gray, Warnock, Good, and Smith).

Common Good Labs analyses of data from the East Baton Rouge Parish School System.

What does the research say about the relationship between reading proficiency by the end of third grade and academic achievement, college retention, college and career readiness, incarceration, and high school dropout?

Common Good Labs analyses of data from the East Baton Rouge Parish School System.

Expanding Access to Quality Early Care and Education in EBR Parish (Resourcefull Consulting).

Common Good Labs analyses of data from the East Baton Rouge Parish School System.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Common Good Labs analyses of data from the Louisiana Department of Education.

Proven Benefits of Early Childhood Interventions (Karoly, Kilburn, and Cannon).

Ibid.

Ibid.